Forgotten No More: Will Burtin, Pioneer of Infographics

Will Burtin, a German designer who refused an art director position with Hitler and his propaganda machine, became a pioneer of infographics in the US. I confess that I did not know of him until I learned of the recent Kickstarter campaign for funding the new book, Will Burtin: Journey to Understanding, written by R. Roger Remington and Sheila Pontis. His work blew me away – forward thinking, intelligent and beautiful.

On a deeper dive through the RIT Libraries, Wikipedia and more articles, I discovered that Burtin left Europe pre-WWII, eventually landing at the US Federal Works Agency where he learned 3D design – which would become a critical component of his work to come. While teaching at SVA, he was drafted into the army and began designing instructional manuals for new recruits. By creating wordless diagrams, he shortened the training period significantly.

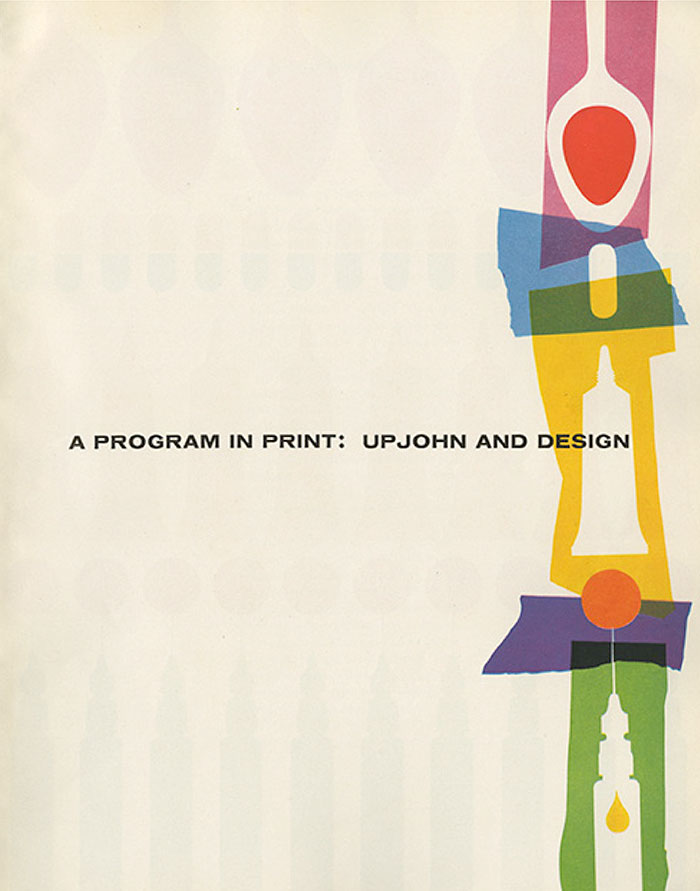

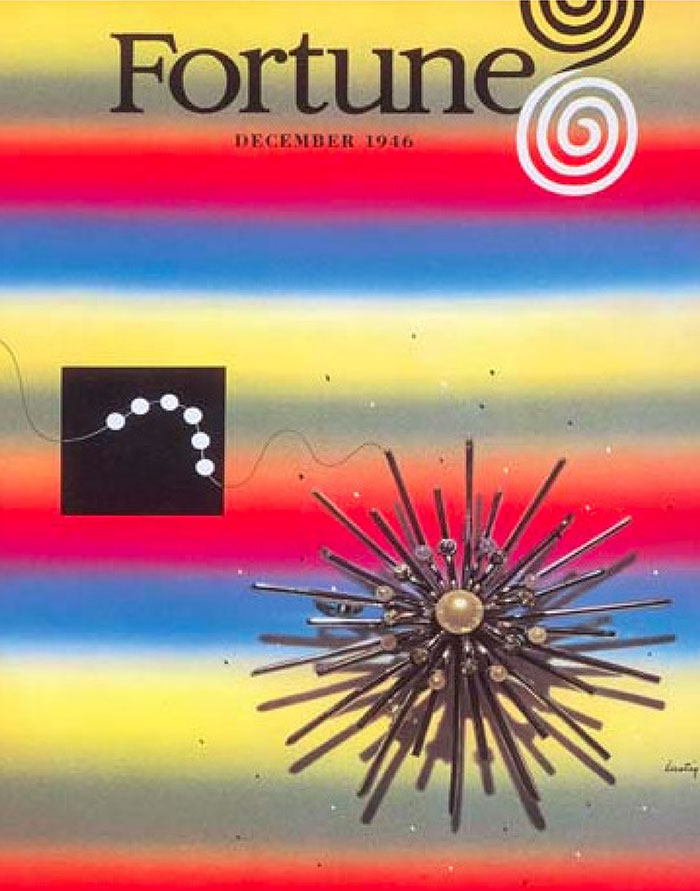

On his return to the States, Burtin worked for Fortune Magazine while establishing freelance partnerships with Eastman Kodak, IBM, the Smithsonian, Union Carbide, Herman Miller Furniture, and perhaps his most important relationship with the pharmaceutical giant Upjohn, where he would work until his death in 1972.

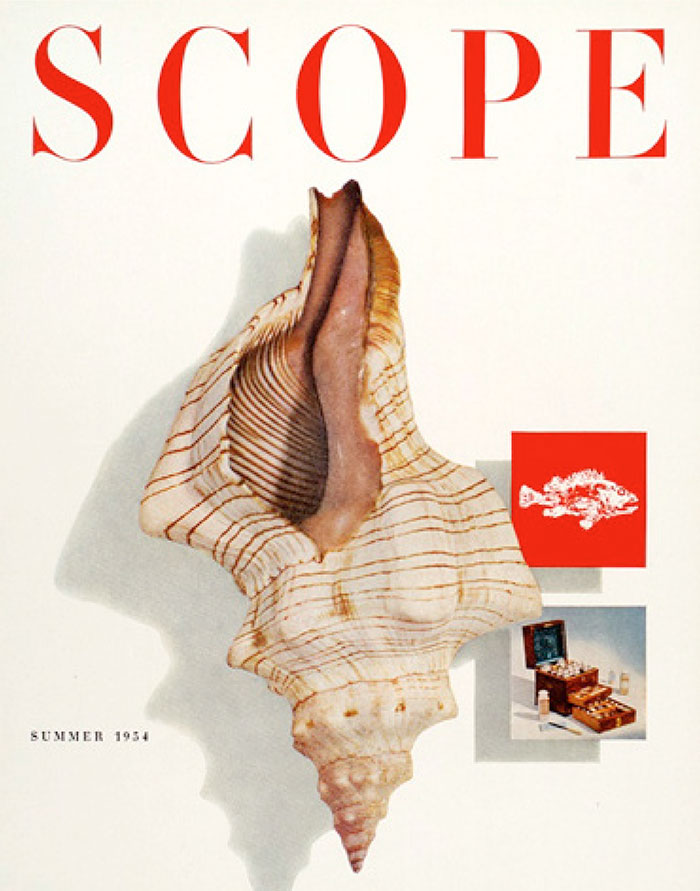

Burtin designed Scope at Upjohn, its magazine dedicated to medical, scientific and pharmaceutical information, and the ground-breaking exhibit, The Cell – making seemingly impenetrable scientific information accessible to all – among many other installations that rival today’s interactive strategies.

A Revolutionary Approach to Design

With his vast knowledge of industrial and graphic design across many industries, Burtin was able to merge design, art, research, science and technology into an innovative and clear visual language – the information design we know, and rely on, today. Boundless and using all the tools in the box to solve the challenge, he was indeed a revolutionary among mid-century designers. I believe he would be considered so today as well.

One of my heroes, Bradbury Thompson may have been influenced by Burtin, or at least was a contemporary. While their industries differed, their masterful use of form, color, typography, and photography in their overall communications echoed each other.

Book publisher Adrian Shaughnessy states, “His [Burtin’s] ability to turn technical details into accessible but always elegant visual material is as relevant today as it was in the sixties.”